What Is the Comparison the Movie Makes to the Relationship Between Mother and Unborn Baby

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

A community perspective on the function of fathers during pregnancy: a qualitative study

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 13, Article number:lx (2013) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Groundwork

Defining male involvement during pregnancy is essential for the development of future research and appropriate interventions to optimize services aiming to better nascence outcomes. Written report Aim: To define male interest during pregnancy and obtain customs-based recommendations for interventions to ameliorate male involvement during pregnancy.

Methods

We conducted focus groups with mothers and fathers from the National Healthy Kickoff Association program in society to obtain detailed descriptions of male involvement activities, benefits, barriers, and proposed solutions for increasing male interest during pregnancy. The bulk of participants were African American parents.

Results

The involved "male" was identified every bit either the biological father, or, the current male partner of the pregnant woman. Both men and women described the ideal, involved begetter or male partner as present, accessible, available, understanding, willing to acquire nearly the pregnancy process and eager to provide emotional, concrete and financial support to the woman carrying the child. Women emphasized a sense of "togetherness" during the pregnancy. Suggestions included creating male-targeted prenatal programs, enhancing current interventions targeting females, and increasing healthcare providers' sensation of the importance of men'due south involvement during pregnancy.

Conclusions

Individual, family, community, societal and policy factors play a role in barring or diminishing the involvement of fathers during pregnancy. Hereafter inquiry and interventions should target these factors and their interaction in lodge to increment fathers' involvement and thereby improve pregnancy outcomes.

Background

Paternal interest (PI) has been recognized to take an impact on pregnancy and infant outcomes [1–6]. When fathers are involved during pregnancy, maternal negative health behaviors diminish and risk of preterm birth, low birth weight and fetal growth brake is significantly reduced [i–iv, 6]. PI has also been associated with babe mortality upward to one year after nativity [2]. When these findings were stratified by race, several studies written report that the risks of adverse nascency outcomes and subsequent infant bloodshed were markedly college for African-American mothers [one, two, 4, 7].

Whether measured through proxies such as paternal information on birth certificates, maternal written report of paternal activities (back up, presence at pregnancy-related health appointments), or marital/partnership status, findings point to the of import contributions fathers can make to improving birth outcomes [i–4, 6–9]. Researchers take proposed that the mechanisms through which PI affects birth outcomes are primarily linked to the touch fathers tin accept on influencing maternal behaviors and reducing maternal stress through emotional, logistical and fiscal support [6]. For case, meaning women with involved partners have been found to be more than probable to receive early prenatal intendance and to reduce cigarette smoking [9, x]. Other studies have suggested that back up from fathers serves to alleviate the burden of stress [three] and improves maternal wellbeing, both pathways to improved nascency outcomes [eleven, 12].

Despite the bear witness that PI during pregnancy is of import, in that location is a dearth or knowledge which continues to hinder progress towards understanding the role of fathers during pregnancy and the subsequent development of appropriate measurements, of policies and of interventions to increment PI during pregnancy [13]. Given the lack of consensus among researchers about what it means to be an "involved father" and to identify the specific roles of a father during pregnancy, this report sought the perceptions of fathers and mothers themselves. Defining and describing male involvement during pregnancy is essential for the evolution of future enquiry and to inform advisable interventions to increase male involvement.

Methods

In an effort to inform next steps for the National Good for you Offset Association'due south "Male Involvement - Where Dads Matter" initiative, this research projection was designed and executed by a workgroup of concerned fathers, mothers, and maternal and child health specialists. Members included community members, grassroots organization leaders, and academic researchers with the same vision of further delving into the outcome of the office of fathers during pregnancy in order to meliorate inform initiatives aiming to improve the health of infants. Thus this projection is rooted in the principles of community based participatory research, in which central community stakeholders are involved in the formulation of the research question and consequential research execution and programme development [14–17]. Furthermore, community based participatory inquiry (CBPR) is action oriented and serves the dual purpose of both a service to the community in which it is being performed and a research endeavor [fifteen, 17]. In low-cal of the circuitous social underpinnings of factors that determine a begetter's involvement in his child's life, CBPR, with is fundamental inclusive approach of both researcher and community stakeholder, was a necessary approach to further delving into the issue.

Procedures

The research and focus group protocols were developed past the research workgroup and approved by the University of Rochester Medical Eye Enquiry Subjects Review Lath (RSRB 00036193), to ensure the protection of the subjects participating in this research.

The study population was recruited from the puddle of mothers and fathers attending the National Healthy Start Association conference held in Washington, D.C., from March half dozen—ix, 2011. Registered members of the conference were recruited via an electronic mail bulletin describing the study and requesting their participation in focus group discussions. Additional recruitment was conducted at the conference through announcements during plenary sessions. The primary claiming encountered during recruitment was the high no-show charge per unit of males despite initial agreement to participate. To increase male participation, announcements were made during briefing sessions to remind males of the opportunity to share their opinions. All participants were required to sign written informed consent every bit approved by the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board. All persons targeted for recruitment and after enrolled were above the historic period of 21. Participants provided verbal consent and were bodacious that they were not obligated to bring together in the discussion and could cease to participate at any indicate during the focus group. Information drove consisted of v focus group discussions, including i all female person group, 1 all male group, and 3 mixed-gender groups. Additional focus groups were non completed as saturation was reached with the current sample. Near of the participants were African American and parents of one to 5 children. Focus groups were conducted by 3 trained lead moderators, sound-recorded and and so transcribed for analysis. The primary objective of the focus groups was to obtain mothers' and fathers' thoughts on the function of the begetter during their partner's pregnancy to inform adjacent steps of the National Healthy Start Association's fatherhood initiative.

Focus group protocol

The perceived role of males/fathers/partners within the context of heterosexual relationships was the focus for this study. The protocol included questions regarding: 1) the characteristics of the ideal male/partner/father during pregnancy; ii) definitions (father, male partner, biological father, etc.); three) specific activities the ideal father might undertake; iv) differences between the ideal and reality; v) benefits and barriers to paternal involvement; 6) recommendations for addressing those barriers; and seven) additional themes raised by participants. Squad members met following the outset focus grouping to talk over the process, content, and whatever problems that arose. No changes were made to the protocol questions.

Participants

A total of 50 mothers and fathers participating in National Healthy Commencement Association pre- and post-natal health services (Northward = 37 females, N = 13 males) took part in the focus group discussions. The bulk were African American (N = 43). Socio-economic data was not collected due to the nature of focus groups. Participants were from one of 102 National Salubrious Beginning Association sites across the U.s.a., providing a range of income and didactics levels and geographic regions [18]. Although there were 2 gender-specific groups and iii mixed groups, there was consensus within and between all groups regarding the role of fathers.

Analysis

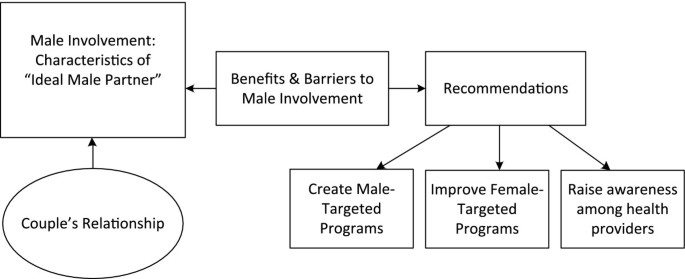

Content and thematic analyses were conducted from transcriptions of the focus groups recordings. All members of the inquiry group participated in examining and interpreting findings. Content analysis consisted of identifying the particulars: specific roles of fathers/men and specific barriers to involvement. Thematic assay enabled the extraction of general themes regarding fathers during pregnancy. Past definition, a theme is a design constitute in the information that at the minimum describes and organizes possible observations or at the maximum interprets aspects of the phenomenon [19]. Thematic analysis is widely used in qualitative research and is an inductive procedure based on direct observation of patterns yielded from the interview information particulars in this example and the interpretation of these patterns to more efficiently organize the data [fourteen, 19, twenty]. The themes identified circumduct around detailed descriptions of the role of males during pregnancy, concerns regarding male interest during pregnancy, too equally recommendations for addressing the issues raised (Figure 1). Findings are presented in the following section, and, as much as possible, participants' words have been retained and presented in italics.

Focus group data categories. This catamenia chart demonstrates the major categories into which the focus grouping data was demarcated and the relationship betwixt the categories. Categories were derived from the group of major themes and synthetic via consensus amongst authors and community partners to more than efficiently organize the data for assay.

Results

Role of male partner vs. biological father

It was initially important to identify the "father" or "male person partner" prior to moving forward with descriptions of paternal involvement. Focus group participants recognized that the "ideal" state of affairs is that the "love partner" and the "biological male parent" are the same person; nevertheless, they recognized that this is not e'er the case. There was a general consensus that, should a human being go involved with a pregnant woman, he would also take partnership in the pregnancy, "fill the gaps" of an uninvolved biological male parent and support her through the procedure. Therefore the expectations of a "love partner" are similar to that of the ideal biological father.

"I don't see any difference, because if yous're gonna be participating, or be a part of the child's life, and likewise along with the expectant mother, then y'all are assuming these roles as a father, a dad, a caregiver." [Male]

The participants besides had clear definitions almost the diverse roles a male tin can take. A "Daddy" was described by the women as "someone who comes and goes," the "sperm donor," or the "biological father." On the other hand, a "Father" is the male who nurtures and raises the child, regardless of the biological relationship. Finally, a "Man" is someone who "steps up" and raises another man's child (which they recognized to exist a growing tendency). Women practise non desire a "Daddy;" they want someone who will be a "father" or a "man." The men agreed with the definition, but insisted that taking care of another human's child is non to be seen as an obligation or a requirement for beingness a "man," but rather every bit a caring human action.

Characteristics of the "ideal" father

Participants were very specific regarding the characteristics of an "platonic father" during pregnancy and provided details regarding activities demonstrating ideal involvement. The ideal male parent is present, accessible and available, an active participant during the pregnancy. He is present at prenatal visits, ultrasounds, Lamaze classes, parenting classes, in the commitment room cutting the umbilical cord, and helps with nascency-related paperwork.

"He's going to the appointments, and he is accessible and available… When I call, he answers…he comes. And when he's there, he's there. He's present." [Female person]

However, apart from the expectation for the partner to be present, respondents emphasized the need for him to exist an active participant in the pregnancy process.

"From going with her to the start ultrasound, the first doctor'due south visit; each time they go he should be a role of that and encourage her. … not just a standby, but actually a participant." [Female person]

An active male parent cares about the pregnancy, asks questions of the mother and healthcare provider, and is eager to acquire more about the process and what is required for a good for you pregnancy. Further, a father provides physical and emotional support to the woman carrying his child. He helps the mother make important decisions such equally creating a nativity programme or choosing a proper name for their child. He encourages the mother and provides positive affirmation about her body image and reassures her most her ability to be a good mother. He knows almost the changes in her body and understands the influence of hormones. He empathizes with her and is patient with her, remaining calm when her emotions fluctuate. Simply listening to her and allowing her to vent provide great emotional relief to the mother.

"His role should be one of an encourager…[Giving] positive affidavit … build her confidence then that she can embrace this new [challenge and that] they can cover it together as a unit of measurement." [Female]

Both men and women participants emphasized this idea of "togetherness" during pregnancy and beyond, which offers groovy security for the female parent. It is the idea that there is an equal investment and interest in having the kid, and that the required responsibleness of having the child is willingly shared between the two parents. This is important so the woman can feel she is not lone.

"It's our baby, not just my baby…Nosotros accept to go through this together and not everything just towards me. Not me just going to the doctors, nosotros need to get through all this together." [Female]

The ideal male parent is too a comforter and caregiver, making certain she feels as comfy every bit possible. Examples participants provided include: "he rubs her anxiety," "does midnight runs to satisfy her cravings," "takes her shopping and to the movies." Respondents besides described how the platonic father is supportive in the physical environment, the habitation. He helps with the cooking, cleaning, washing clothes/dishes, and taking care of the other children in the dwelling. They recognized the importance of the father in encouraging good for you behaviors during pregnancy, helping her manage her diet and exercise during the pregnancy: ensuring that she eats a balanced and good for you diet, taking her for walks, exercising with her.

"Making sure she eats healthy, go to her doctor'due south appointments. If she has to have off because of a high risk pregnancy, he'll maintain the bills, or other kids, if at that place are other kids, just whatever is needed." [Male]

Interestingly, in all five focus group, financial back up was not brought upwards by male or female participants until the moderator specifically asked virtually information technology. This indicates that, contrary to pop belief that men are seen primarily as the financial provider, it was not at the forefront of their thinking about fathers' role during pregnancy. When asked virtually it, participants indicated that financial support is of import, however, emotional and physical back up is crucial during the pregnancy menstruum. Ideally, he would help maintain the bills and stay employed. They specified that men should be involved regardless of their power to provide fiscal back up. Overall, the platonic begetter is seen as the protector who does what is necessary to ensure the safe journeying of the baby and the mother.

"The role of a protector is very important, because if he understands how cigarette smoking tin bear on her, if he'due south smoking, then he should understand the impact that it has on wanting to protect both his partner and the unborn kid. So I meet his role as protecting to ensure a rubber journeying." [Male]

To adequately cover all of these characteristics, respondents felt strongly the platonic father must be responsible and mature. He must have a sense of responsibility for caring for the child and possess the maturity to acquit out the requirements of the office. Here the issue of historic period comes into play, as participants recognized younger fathers are not always well prepared to handle the emotional responsibility that comes with expecting a baby.

Defining male person interest

In addition to characterizing the platonic begetter/partner during pregnancy, participants were asked to define a father'southward involvement during the pregnancy menstruation. The following 2 definitions were specifically verbalized at the conclusion of the discussions, with the grouping members deciding the appropriate wording and like-minded with their concluding statement:

"The part of a man during pregnancy is to be nowadays, to back up, to understand, to be patient, and to have sympathy for the woman carrying his child."

"The role of a man during pregnancy is to provide emotional, physical and (if possible) financial support to the woman conveying his child."

Couple's relationship

An important concept raised in the focus groups was the "love relationship" betwixt the couple - the female parent and the father or male partner during pregnancy. This relationship was cited as pivotal in terms of male involvement in the pregnancy. While many women mentioned this every bit the platonic or preferred state of affairs, male participants also emphasized their human relationship to the mother would make up one's mind the level of their involvement during the pregnancy procedure.

A female participant explained: "If I'm pregnant and I have this meaning other,… and I tell them, you know, 'Be with me,' that's the main thing, 'But exist with me' during this fourth dimension." A male person participant resonated the sentiment that the "man will treat that child in an equal proportion to how he feels virtually the woman."

The emotional or romantic connexion (or lack thereof) tin heavily influence the level of involvement past the father likewise as the mental well existence of the female parent both during and later on pregnancy. The following annotate by a male person participant explains the dilemma that men face when he fathers a child with a woman whom he feels little emotional connection:

"When my wife was pregnant, I was at all the appointments…so I was there…I think it depends how yous feel most that girl…[If] you lot just got some random chick meaning you're not going to experience like going to an date with her, yous're not going to feel like, encouraging her. It's like, 'Man I can't believe I got this chick meaning.'…He needs to detect some support for himself to be like, 'you have to do this', it has to be some kind of encouragement for him." [Male]

Being romantically involved with the mother was cited as contributing to her emotional well existence and of import in relieving the bouts of depression that can occur in pregnancy.

"Since he's not in the picture, for a woman, automatically, she's depressed. I don't know too many women who are pregnant and want their human being to non exist there. Normally she wants him there and just the near presence of knowing he is notwithstanding a part reduces your stress level." [Female]

Information technology also contributed to her feeling of security that this person will exist there even after the pregnancy.

"She wants to know that he's in this too as she is, and that parenting is a 2-fashion street. It'due south not but nigh mom. And mom needs to know that he's going to exist in that location later and provide the aforementioned beloved and support that he's providing when she's pregnant." [Female]

During the discussion men and women highlighted that often, the couple's relationship takes precedent over focus on the child. Every bit 1 female respondent put information technology: "Nobody thinks about that baby. No 1 thinks about [it being] their pregnancy. All they see is the mom, dad, and the relationship." The full general consensus was the focus should be primarily on the child, regardless of the status of the couple's relationship.

In the give-and-take surrounding the couple's relationship, participants often stressed the significance of healthy communication between parents. Largely they felt that "communication beforehand," or in the early stages of the human relationship prior to conception can have important implications to how the pregnancy feel is managed. Another attribute raised is the differences in advice styles. Women felt men often cannot articulate their feelings well and are non as open to sharing [their emotions] thus straining the parental relationship. In contrast, men felt women ofttimes were loud and accusatory when they attempted to talked with them.

"Men and women aren't the same. Men have a difficult time communicating. We don't communicate well with each other. And we certainly cannot express feelings." [Male]

Benefits of fathers' involvement

The chief benefits of having a father or male partner involved during pregnancy were the reduction of maternal stress levels and the encouragement of positive maternal behaviors. Participants believed these to have implications for the wellness of the baby. They reasoned that if the mother's physical and mental health was optimal, then the benefits would be observed in the baby.

"Be agreeable, have less stress off of her cause by her being an African black adult female, infant mortality rates is high, and if you put all this stress on her, it'south putting stress on the baby." [Female]

Indeed, African American participants in particular were very aware of the higher rates of infant mortality within their community compared with others. They strongly felt that if fathers would be more involved and help reduce maternal stress levels, it would positively affect baby outcomes. Participants expressed that African American mothers equally a group are more vulnerable to lack of PI:

"I remember especially in African-American community nosotros have besides many single parents. We accept far too many. Not simply that, the divorce rate is loftier in African-Americans besides so we demand to establish strong relationships and build stronger marriages." [Female person]

Barriers to fathers' involvement

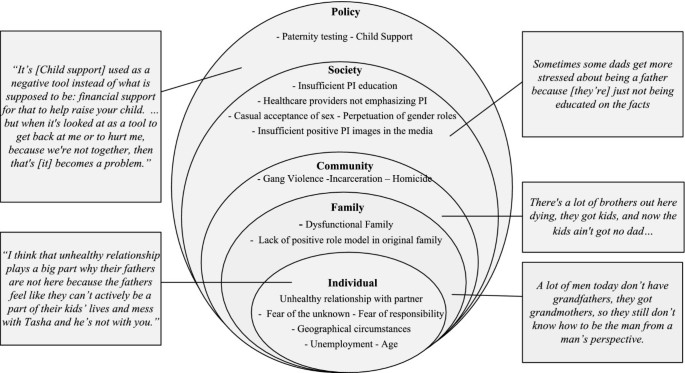

Participants recognized that at that place are sadly, many barriers to fathers' involvement during pregnancy. These can be broadly categorized using Bronfenbrenner'due south socioecological model [21] (Figure 2).

Barriers to fathers' interest during pregnancy. In this figure we dissect the barriers to begetter'southward involvement by levels in the socioecological model. Inside in each sphere of influence starting from the individual and extending out towards the policy level, detail is provided about the potential barriers categorized at this level as revealed in the focus group information. Actual quotes from participants are inserted at each level to provide examples.

As displayed in Effigy 2 participants indicated that the major deterrents to begetter'south involvement at the private level are: an unhealthy relationship between the father/male person partner and the biological mother, and men in general non knowing their office or non wanting the new responsibilities (financial and time) associated with having a kid. They attribute this largely to general lack of education available for expecting men, lack of positive office models in the family sphere, and dysfunctional family foundations. The expense and insufficient availability of paternity testing can too be a deterrent for involvement if the human questions the legitimacy of the child existence his. A lack of understanding of the function of Kid Back up and lack of noesis of regulations and legal financial responsibilities were likewise cited as significant obstacles to men'south interest.

Participants too bemoaned the popular public credence of casual sexual encounters which belittles the role of parenting. Participants felt that males do not adequately set up for the possibility of pregnancy. Furthermore, they believed that societal, perpetuation of gender roles places the responsibility of caring for children on women. Men are expected to provide financially, simply media based stereotypes, are not obligated to provide emotional or physical support. Participants wished examples of men being good fathers were better marketed. In improver, participants felt that social issues such as involvement in gangs and violence contributed to absent fathers through incarceration or homicide.

Of note, participants commented on the importance of the human relationship of the father and the female parent'southward family. Specifically, respondents felt that if the mother of the mother, i.e. the grandmother, fostered an accepting relationship with the biological father he would be more apt to be involved in taking care of the mother and the coming child. This is in line with family systems theory, which posits that cross generational triangulation patterns can reverberate across generations [22].

In sum, participants viewed interest of fathers during pregnancy time equally very positive for the female parent and the kid. However, they as well recognized many prevailing barriers to a homo fully realizing his role as an expectant father.

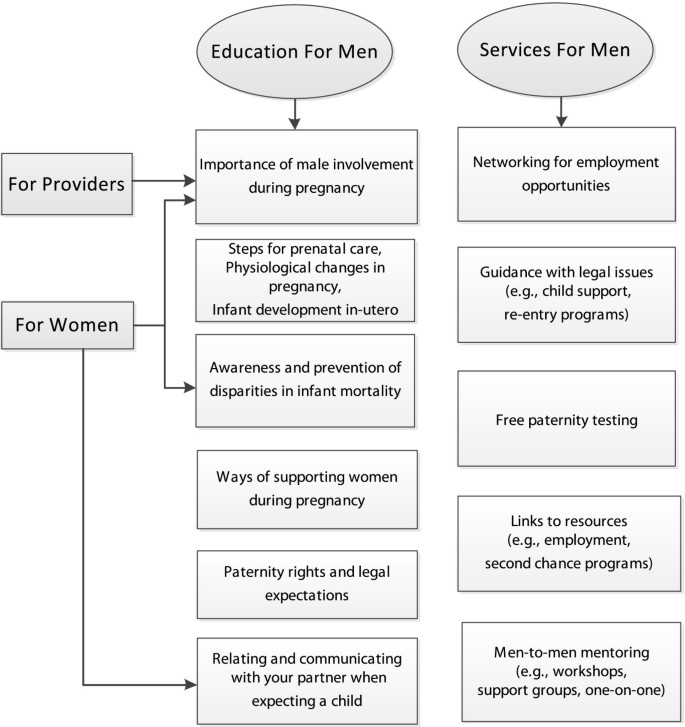

Community recommendations for increasing fathers' involvement during pregnancy

Participants identified a number of strategies that could increase the involvement of men during pregnancy. Effigy three displays these recommendations by target populations including women, men and health care providers. Primarily, participants were unanimous that at that place needed to be pedagogy for men to increase their knowledge of paternity rights and expectations, likewise as the pregnancy procedure. Alongside educational efforts, participants desired interventions that provided men with links to vital resources (paternity testing, information on child support regulations, second take a chance programs) and employment opportunities, especially for those with a disability or previous incarceration. Participants also emphasized that health care providers and women besides demand to appreciate the involvement of men during the prenatal period and its touch on on maternal and child health. Finally, participants recognized the importance of providing support and training to men and women, especially communication skills, that might strengthen their relationship as it pertains to the kid's needs.

Recommendations for programs aimed at improving pregnancy outcomes by increasing male interest. Recommendations were provided throughout the focus group information and focused mainly on teaching for men and the services that should be provided to promote platonic paternal involvement. Included were suggestions for education and/or services targeting women and service providers.

Give-and-take

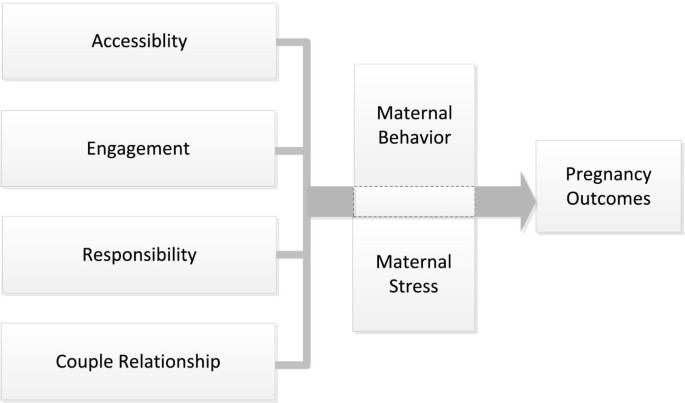

In this study, an involved human being or father during pregnancy is defined past participants as being attainable (eastward.g., present, available), engaged (e.g., cares most the pregnancy and the coming child, wants to learn more near the process), responsible (due east.k., is a caregiver, provider, protector), and maintaining a human relationship with the adult female carrying the child, regardless of their ain partnership condition. This is partly in line with findings on interest of fathers with children, particularly Lamb's theory which posits three components, engagement, accessibility, and responsibility, which associate moderately with each other and decide the degree of involvement of the man [23]. These dimensions refer to father-child relationships. Based on this study's findings nosotros aggrandize this theory in the context of pregnancy, riding on the supposition that both the mother's and the father's office began with insemination, through pregnancy and continues later on the birth of the child. These concepts would and so be practical to the father in relation to the mother carrying the child. Paternal involvement during pregnancy, though similar to paternal interest during childhood, has a specific deviation which nosotros identify equally the relationship betwixt the father and the mother carrying the child. We therefore suggest that paternal involvement during pregnancy is composed of four elements (accessibility, engagement, responsibility, and couple relationship) which may lead to positive pregnancy outcomes through the reduction of maternal stress [3] and back up for positive maternal behaviors [6, 9] (Figure 4). The couple relationship element is intertwined inside each of the commencement 3 components of paternal involvement during pregnancy.

Model for fathers' involvement during pregnancy. The model conceptualizes the 4 components of a proposed framework for paternal involvement during pregnancy. The model reflects similar elements to Lamb's theory of paternal involvement in childhood (accessibility, responsibility, appointment). In pregnancy, the extent of these cardinal characteristics is mediated by the nature of the human relationship between the mother and the male person involved.

Accessibility

Participants honed in on the terms nowadays, attainable and bachelor to depict one level of male involvement during pregnancy, which aptly encapsulates the concept of Accessibility referred to by researchers in the field of childhood development [23–25]. During childhood, accessibility refers to the begetter being physically present and available to supervise the child, just non actively participating in the same activities as the child. For instance the male parent may be at the playground observing the child, only not playing with the child [23, 25]. In a like vane, our report participants felt that the father's concrete presence both in the abode (ideally) and at prenatal activities is associated with achieving the perception of parental "togetherness" in the pregnancy process. All the same the father's willingness and/or ability to embrace this notion of Accessibility is heavily dependent upon his human relationship with the mother. Similar to parents raising a child, the quality of the parental relationship often impacts subsequent involvement with the child [26–28]. Communication between parents, whether prenatally or postnatally, is of import to ensuring that fathers are involved. This becomes even more crucial when parents are not in the same household. Research on divorced parents, shows that fathers' postnatal involvement with their children diminishes profoundly due to breakdown in the parental relationship, poor communication [29] and loss of paternal satisfaction [xxx, 31].

Engagement

The 2d component of the framework for fathers' interest in babyhood is engagement. In infancy, engagement is the directly interaction of the begetter with the child, playing with him, reading books to the child etc. [23–25]. In pregnancy however, this interaction is directed towards the mother and requires active participation in prenatal activities (e.m. reading prenatal care books and request questions at prenatal intendance visits). Analogous to paternal involvement in kid rearing, in pregnancy the coaction betwixt Accessibility and Date is a rhetorical relationship. Every bit the father avails himself to the female parent by existence physically present, the expectation for him to also exist an active participant or actively engaged in the prenatal process becomes evident. Lamb's framework suggests that accessibility without the ensuing components of engagement and responsibility constitutes an incomplete structure to paternal involvement that volition deprive the child of critical support needed for healthy development and emotional well being [23, 32]. Pregnancy parallels this equally it has been indicated that the lack of male person involvement is strongly correlated with college baby morbidity and mortality [vi, 33, 34], reinforcing the need for constructive strategies that seek to increase men'south involvement prenatally. However, as our written report confirms, the caste of involvement is proportional to the quality of the human relationship with the mother and the parent's desire for the pregnancy [9, 27, 34, 35]. This is consistent with our model that places Engagement in the context of the couple's relationship.

Responsibleness

Responsibility embodies the multifaceted roles that fathers/male partners play in financially supporting the kid from birth [23, 25]. Nevertheless, prenatally, this responsibleness towards the coming child is directed towards the mother carrying the child and extends beyond finances. In our written report the concept of Responsibility was manifested in the father assuming the roles of caregiver, provider, nurturer and protector. Community members recognized that men's involvement is a protective factor that helps to ease maternal stress and to encourage positive maternal behaviors. This has been demonstrated in the literature on pregnancy outcomes. Women whose partners were involved in their pregnancy were more probable to receive prenatal intendance [ix, 34], and less likely to requite birth to depression nascence weight and premature infants [33, 34] and to promote positive maternal behaviors [9]. Although fathers' interest has been accounted hard to measure, there is consensus that women with more support from their partners tend to have healthier babies. Similar to Accessibility and Engagement, Responsibleness is embedded in the context of the parental human relationship since discordance in the parental rapport can impinge on the father's willingness or ability to act responsibly.

Many other socio cultural factors may touch fathers' interest during pregnancy. Every bit highlighted in our study, lack of substantive preconception and prenatal teaching for men, consequent undervaluing of fathers' involvement by health care providers, and dysfunction in the fathers' (or mother's) family of origin often atomic number 82 to ambiguity regarding their part as fathers and its significance [27, 36]. The predominance of social messages that highlight the mother'southward function in child rearing while negating that of the male parent besides compounds the issue of male parent absenteeism or disillusionment [27, 37]. Further, social media images oft promote coincidental sexual encounters without adequate contraceptive messages or letters regarding paternal responsibility in the event of an unintended pregnancy; this creates an atmosphere that can increase the occurrence of pregnancy (in adolescents) [38] as an unplanned and untimely event, which has been shown to decrease the level of fathers' involvement [9, 34].

Strength and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the get-go study that attempts to narrate fathers' involvement during pregnancy, apply theoretical models to understanding the results, and suggest a new model for further testing. The employ of community based participatory research to develop and implement the research project is an important aspect that lends additional credence to the study findings. This study is a crucial showtime stride for developing measures of paternal involvement and for developing programs to increment fathers' involvement during this crucial time for infants, in-utero. A limitation of the report is that participants were limited to those who attended the National Salubrious Kickoff Association briefing. Of note is that funding was given across sites to aid ensure that those who could not afford information technology would still be able to participate, ensuring representation across sites as well as across socio-economic condition.

Initial data on fatherhood during pregnancy tin but be gathered through in-depth conversations with parents and those involved in the day-to-day piece of work with families. Our study provides the footing for larger studies that will take a broader and more than holistic approach to family health, regardless of the composition of the "family," in club to improve health outcomes for mothers and infants.

Recommendations

In calorie-free of the affect of fathers' involvement on maternal and babe health, as identified in the scientific research as well equally this community investigation, information technology is crucial that interventions and policies to better baby outcomes prioritize fathers' involvement [34, 36, 39]. Of great importance is the training of health intendance providers to stress the need to encourage and welcome fathers in the prenatal process, every bit they are in a primal position to be influential to the mother's wellness beliefs [40]. Nonetheless males must first be educated most specific expectations of a father, the importance of his role to healthy child development and how he tin can best support the female parent to improve pregnancy outcomes [36]. Information on biological changes in the mother and bug surrounding risk factors for baby mortality would also be integral components of whatever proposed educational curriculum. To have greater bear upon, this education process should brainstorm prior to conception and should exist targeted specifically to males, addressing their distinctive concerns [26, 36, 41]. Furthermore, though there are existing parenting programs that provide support for new parents, these often lack the comprehensiveness of co-parent counseling support, male person merely counseling, resource support (due east.g. employment opportunities) [26], and guidance in legal issues such equally kid support and paternity testing [41]; all of which are urgently needed. A one-on-one male mentoring approach would also be helpful in teaching males how all-time to fulfill their role, every bit this community group has highlighted. Improving existing prenatal services for women should as well be modified to include information on the importance of paternal involvement to infant health outcomes. Importantly, improved communication skills are crucial to developing better relationships betwixt parents and facilitate increased male interest to benefit the child.

Conclusions

Paternal interest is as crucial prenatally as it has been shown to exist postnatally for infants. Fathers are to be attainable and engaged during the pregnancy and begin to demonstrate responsibility towards the coming child past helping the mother. Because all of the involvement is through the mother conveying the child, the relationship betwixt the two parents is of utmost importance and determines the level of involvement. Of note, is that while in the postnatal phase, the financial ability of the father is of paramount importance [26, 32], the financial support appears to be much less emphasized during pregnancy when compared with emotional and physical support. Instruments to assess father involvement during pregnancy should include a measure of parental relationship, simply every bit interventions to increment fathers' involvement must program for addressing relational factors between parents regardless of their marital status.

Despite participants' understanding of the importance of PI for maternal health and behavior as well as baby nascency outcomes, many barriers to optimal involvement were identified. Private, family, community, societal and policy factors play a role in barring or diminishing the interest of fathers during pregnancy. Future research and interventions should target these factors and their interaction in social club to increase fathers' involvement and thereby improve pregnancy outcomes.

References

-

Alio AP, Kornosky JL, Mbah AK, Marty PJ, Salihu HM: The bear on of paternal interest on feto-infant morbidity amidst whites, blacks and hispanics. Matern Child Health J. 2010, 14 (five): 735-741. ten.1007/s10995-009-0482-1.

-

Alio AP, Mbah AK, Kornosky JL, Wathington D, Marty PJ, Salihu HM: Assessing the bear on of paternal involvement on racial/ethnic disparities in baby bloodshed rates. J Community Health. 2011, 36 (1): 63-68. 10.1007/s10900-010-9280-three.

-

Ghosh J, Wilhelm Thousand, Dunkel-Schetter C, Lombardi C, Ritz B: Paternal support and preterm nascence, and the moderation of effects of chronic stress: a report in Los Angeles County mothers. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010, xiii (four): 327-338. x.1007/s00737-009-0135-ix.

-

Ngui E, Cortright A, Blair M: An investigation of paternity status and other factors associated with racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes in milwaukee, wisconsin. Matern Kid Health J. 2009, 13 (4): 467-478. ten.1007/s10995-008-0383-8.

-

Alio AP, Bond MJ, Padilla YC, Heidelbaugh JJ, Lu M, Parker WJ: Addressing policy barriers to paternal involvement during pregnancy. Matern Child Health J. 2011, 15 (4): 425-430. x.1007/s10995-011-0781-1.

-

Padilla YC, Reichman NE: Low birthweight: Exercise unwed fathers help?. Kid Youth Serv Rev. 2001, 23 (4–five): 427-452.

-

Misra DP, Caldwell C, Young AA, Abelson South: Do fathers matter? Paternal contributions to birth outcomes and racial disparities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010, 202: 99-100. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.xi.031.

-

Alio AP, Mbah AK, Grunsten RA, Salihu HM: Teenage pregnancy and the influence of paternal involvement on fetal outcomes. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011, 24 (vi): 404-409. 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.07.002.

-

Martin L, McNamara Yard, Milot A, Halle T, Pilus E: The effects of begetter involvement during pregnancy on receipt of prenatal care and maternal smoking. Matern Child Health J. 2007, 11 (6): 595-602. 10.1007/s10995-007-0209-0.

-

Zambrana RE, Dunkel-Schetter C, Scrimshaw S: Factors which influence apply of prenatal care in depression-income racial-ethnic women in Los Angeles County. J Community Health. 1991, xvi (5): 283-295. 10.1007/BF01320336.

-

Feldman PJ, Dunkel-Schetter C, Sandman CA, Wadhwa PD: Maternal social support predicts nascency weight and fetal growth in human pregnancy. Psychosom Med. 2000, 62 (5): 715-725.

-

Austin M-P, Leader 50: Maternal stress and obstetric and infant outcomes: epidemiological findings and neuroendocrine mechanisms. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000, xl (3): 331-337. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2000.tb03344.ten.

-

Bond MJ, Heidelbaugh JJ, Robertson A, Alio PA, Parker WJ: Improving research, policy and exercise to promote paternal interest in pregnancy outcomes: the roles of obstetricians-gynecologists. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010, 22 (6): 525-529. 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3283404e1e.

-

Liamputtong P: Qualitative Research Methods. 2009, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, iii

-

Mosavel Grand, Simon C, van Stade D, Buchbinder M: Community-based participatory inquiry (CBPR) in Due south Africa: engaging multiple constituents to shape the research question. Soc Sci Med. 2005, 61 (12): 2577-2587. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.041.

-

Higgins DL, Metzler Chiliad: Implementing community-based participatory research centers in diverse urban settings. J Urban Wellness. 2001, 78 (3): 488-494. 10.1093/jurban/78.3.488.

-

Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB: Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Wellness. 1998, 19: 173-202. ten.1146/annurev.publhealth.nineteen.i.173.

-

Salihu HM, August EM, Jeffers DF, Mbah AK, Alio AP, Berry E: Effectiveness of a federal healthy start program in reducing principal and repeat teen pregnancies: our experience over the decade. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011, 24 (3): 153-160. x.1016/j.jpag.2011.01.001.

-

Boyatzis RL: Thematic Analysis and Code Development: Transforming Qualitative Information. 1998, California, USA: Sage publications

-

Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E: Demonstrating rigor using thematic assay: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme evolution. Int J Qual Meth. 2006, v (1): 80-92.

-

Bronfenbrenner U: The ecology of cerebral development: Research models and avoiding findings. Evolution in context: Acting and thinking in specific environments. Edited by: Wozniak RHFK. 1993, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 3-46.

-

Kerr MEaB Yard: Family evaluation: An approach based on Bowen theory. 1987, New York: W. West. Norton

-

Lamb ME PJ, Charnov EL, Levine JA: A biosocial perspective on paternal behavior and involvement. Parenting across lifespan: Biosocial dimensions. Edited past: Lancaster JAJ, Rossi A, Sherrod 50. 1987, Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter, 111-142.

-

Berger LM, Langton CE: Young disadvantaged men equally fathers. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2011, 635 (1): 56-75. 10.1177/0002716210393648.

-

Peters EDR, Peterson GW, Steinmetz S: Fatherhood: inquiry, interventions and policies. 2000, New York: Haworth Press

-

Lamb ME, Tamis-Le M, Catherine South: The Function of the Father: An Introduction. The function of the father in child development. Edited by: Lamb ME. 2004, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 1-31. 4

-

Lu MCJL, Wright K, Pumpuang G, Maidenberg M, Jones D, Garfield CMD, Rowley DL: Where is the F in MCH? begetter interest in african american families. Ethinicity and Illness. 2010, 20: 49-61.

-

Gee CB, Rhodes EJ: Adolescent Mothers' relationship with their Children'due south biological fathers: social support, social strain, and relationship continuity. J Fam Psychol. 2003, 17 (iii): 370-383.

-

Ahrons CR, Miller RB: The outcome of the postdivorce human relationship on paternal involvement: a longitudinal analysis. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1993, 63 (3): 441-450.

-

Leite RW, McKENRY PC: Aspects of begetter status and postdivorce begetter involvement with children. J Fam Bug. 2002, 23 (5): 601-623. 10.1177/0192513X02023005002.

-

Seltzer JA: Relationships betwixt fathers and children Who live apart: the Father's part after separation. J Marriage Fam. 1991, 53 (1): 79-101. 10.2307/353135.

-

Harris KM, Marmer JK: Poverty, paternal involvement, and boyish well-existence. J Fam Problems. 1996, 17 (five): 614-640. 10.1177/019251396017005003.

-

Alio AP, Salihu HM, Kornosky JL, Richman AM, Marty PJ: Feto-baby health and survival: does paternal involvement matter?. Matern Kid Health J. 2010, 14 (half dozen): 931-937. 10.1007/s10995-009-0531-9.

-

Hohmann-Marriott B: The couple context of pregnancy and its effects on prenatal care and birth outcomes. Matern Child Wellness J. 2009, 13 (six): 745-754. 10.1007/s10995-009-0467-0.

-

Gavin LE, Black MM, Minor S, Abel Y, Papas MA, Bentley ME: Young, disadvantaged fathers' involvement with their infants: an ecological perspective. J Adolesc Health. 2002, 31 (3): 266-276. 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00366-Ten.

-

Outcomes CoPIiP: All-time and Promising Practices for improving enquiry, policy and practice of paternal interest in pregnancy outcomes. 2010, Washington, D.C.: Joint Center for Political and Economical Studies

-

Hewlett SAWC: The State of war Against Parents: What We Can Do for America'southward Beleagured Moms and Dads. 1998, Boston: Houghton Mifflin

-

Chandra A, Martino SC, Collins RL, Elliott MN, Drupe SH, Kanouse DE, Miu A: Does watching Sex on idiot box predict teen pregnancy? findings from a national longitudinal survey of youth. Pediatrics. 2008, 122 (5): 1047-1054. 10.1542/peds.2007-3066.

-

Bond MJ: The missing link in MCH: paternal interest in pregnancy outcomes. Am J Mens Health. 2010, 4 (4): 285-286. 10.1177/1557988310384842.

-

Tweheyo R, Konde-Lule J, Tumwesigye NM, Sekandi JN: Male partner attendance of skilled antenatal care in peri-urban Gulu district, Northern Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010, ten: 53-10.1186/1471-2393-x-53.

-

Westney OE, Cole OJ, Munford TL: The furnishings of prenatal didactics intervention on unwed prospective boyish fathers. J Adolesc Health Care. 1988, 9 (3): 214-218. 10.1016/0197-0070(88)90074-five.

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/13/60/prepub

Acknowledgements

We give thanks the National Salubrious Start Clan for their financial support for this study. Nosotros are besides grateful to the mothers and fathers who and so willingly shared their stories in the focus group discussions. We would like to recognize Michael Morgan, Philip Rowland, Vanessa Rowland Mishkit, Kimberly Alexander, and Hope Tackett from ReachUP, Inc., for their assistance with the planning and implementation of the focus groups.

Author information

Affiliations

Respective writer

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors of this manuscript have no significant competing financial, professional or personal interests that might have influenced the performance or presentation of the work described in this manuscript.

Authors' contributions

APA designed and implemented the written report, conducted the qualitative analyses and was the primary contributor to manuscript evolution. CL shared in the training of the manuscript with Dr. APA and also conducted the qualitative analyses. KS and KH participated in the study design, implementation and data collection, reviewed manuscript and made revisions to ensure that community interests were well represented. KH reviewed and made edits of the manuscript to ensure that the content and construction was in keeping with National Healthy Starting time objectives. KF reviewed the manuscript for accuracy and goals of inquiry projection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Primal Ltd. This is an Open up Access article distributed under the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Alio, A.P., Lewis, C.A., Scarborough, K. et al. A customs perspective on the part of fathers during pregnancy: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13, lx (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-60

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/1471-2393-13-sixty

Keywords

- Pregnancy

- Begetter interest

- Salubrious start and fathers

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2393-13-60

0 Response to "What Is the Comparison the Movie Makes to the Relationship Between Mother and Unborn Baby"

Enregistrer un commentaire